Meeting in the village of Foudou - The floor is earth and the sides are open, the essence of humility

Too dumb to keep but too hard to leave behind

It is March, I am in Dakar and have just been picked up from my hotel to go to the office. The Novotel is a better hotel than i am used to, modern French minimalist. I was upgraded to a room with a sea view but the room is dark, the sea view window is less than half a door in size, I suppose for some eco design reason, and at an angle so you can only see the sea if you stand right at it. I can make most things work and when I can’t it is apparently because i am not thinking enough like a Citroen mechanic. Some room features seem to work better when I try them backwards for example in the bathroom, up means on and down off and green means hot and blue means water flow and things of that nature. Some aspects remain a mystery, like the moulded plywood feature that covers the orange vinyl cushion on the stool under the desk. I arrived last night from Nairobi, the time is three hours behind, so bed was two a.m. and I am feeling it a bit this morning.

My drivers name is Aziz, his English is good and we make ‘morning in the traffic’ small talk.

“So how is the office?”

“The office is very fine”

“How is my friend Brett? “ Brett is originally from Canada and has been working in Senegal for a number of years.

“Brett is very fine.”

“Brett just got married?”

“Yes maybe one month ago and his wife is very beautiful”

“Have you met his wife? “

“Yes she is very tall, she is like the Cooka Cola”

“The Coca Cola?”

“Yeeees, she is tall and has good shape and is very brown.......... like the Cooka Cola.........and she has very good teeth. Aziz said this laughing so that the words and the laughing were all one.

We wind through backstreets of an old part of town, its all an old part, we pass the Hotel Croix du Sud a fine old art Deco style hotel built around 1950 that apparently used to be the best in town. It reminds me the Bakelite radio that my father gave me as a child to listen to the Argonauts on the ABC. We cross Boulevard du General de Galle, and go around Independence Square, which is the size of several soccer fields and in it are low concrete retaining wall instalments painted and sun bleached, un-kept paths and several dry fountains. It has a mad broken garden gnome feel about it. There have recently been some pre-election protest riots around here. We take a road the goes near the old market in an area that translates to something like “Walk of Barrels” and hit the coast.

Now we follow the road from the edge of the city centre along the coast towards the airport, we swerve only to avoid those things that might do us damage. Like donkey carts, or aging yellow Peugeot taxis. Pedestrians run between speeding cars like a dare. The street sign says Route de la Comiche Quest – ‘Road to the Comic Quest’, and I remember Don Quixote and wonder if we all need to be a bit mad to make sense of what is going on around us, not only here but anywhere.

Last time I was in Dakar, Brett took me to dinner along this same road, a clutter of buildings behind a taxi stand in front of little Luna Park that is all painted up like a harlequin hat. The Cafe Sportif is perched on a small cliff overlooking the beach. We arrived at dusk and watched the water turn from aqua to mercury to ink. And we talked about work and Africa and he talked of his upcoming marriage and me of lost loves.

When it came time to came to go, there was a scramble of taxi drivers around us and under coloured light bulbs draped in a tree and somehow we ended up in one of the old beaten up black and yellow Peugeots with a Rastafarian driver , he was high on something, maybe herbs or drink or just on life. A crafts hawker stops me closing my back door desperate to sell me three carved ebony monkeys each about the size of a Russian doll, hear no evil, speak no evil , see no evil. And I didn’t want them but I buy them anyway and pay a quarter the price he started at and still feel I pay too much. We lurch off up the road , the old 505’s diff is wining, the tappets sound like shaking rocks in a tin and the springs and shocks are gone and with every bump we bottom out with a jarring thud and each time I close my eyes, it has an end of the world feeling about it. The driver is shouting at us in French, we make the first corner and both his and my doors fly wide open like it was something they were supposed to do on cue. I nearly fall out but grab the door and slam it back in but the same thing happens at the next right hand corner and I move to the middle of the back seat, holding the back of Brett’s’ passenger seat with one hand and the opening back door with the other. And the driver is grinning and shouting and laughing and I can’t understand a thing he is saying but I am getting him anyway. And when I get back to the hotel room in the light, I see that two of the little monkeys are see no evil, accompanied by one hear no evil. They are too good to throw away, and too dumb to keep, but I pack them anyway. So many things in life seem like this and I am thinking of all the things I hold on to that are no good for me or for others.

My task this trip is work with two new business councils in their rural villages. We have some new Business Facilitators and part of their job will be to form as many as twelve business councils and so I am here to do some training and mentoring while actually in the field working with community groups.

We are in the office I am sitting with my colleague Benedict who is originally from Mali. We are planning the logistics for the week ahead. When I have visited previously the projects are generally three or four hours from Dakar, so if we leave early we can schedule community work in the afternoon.

“So where are we going” I ask.

“Velingara”

“Okay good, and how long will it take us to get there?”

“It is not so far” he says, but his eyes flicker

“Benedict” I say, “how far exactly is it?”

“It is a really beauuuutiful drive” Benedict says looking through me to the wall behind. “It is near the border with Ginea Bissau”

“Okay, how long will this beautiful drive take?” I ask

“Ten hours, but this is a very, very nice drive, a very beauuuutiful drive”

“Ten hours!”

“My broder “he says “everything is possible in Senegal”

And so now it is two days later and we are in a community meeting place in the middle of a small rural village about an hour out of Velingara. We are seated in a shelter that can hold about two hundred people, the roof is a thick grass thatch bound to rafters with rope like raffia held on tree trunks each with a natural fork at the top to hold the rafters. The floor is earth and the sides are open, the essence of humility. People filter in and several men whom I assume are village elders bring traditional chairs, that have the dimensions of a deck chair and made from two wide rough hewn planks that both have a notch taken out about one third of the way along, to half the width, and so fitted together they form an off centric cross with the short side forming the seat and the longer the longer the back rest.

After about half an hour we start the meeting and I gather that about ten years ago we bought a large plot of land along the bank of the passing river for some struggling farmers and helped them develop it into a communal banana plantation. We provided big diesel pumps to irrigate from the river, the banana plants, the fertiliser and training. And when fences were needed to keep livestock and wild donkeys out we provided the materials. And for a while apparently this was a model project. And then as one thing or another went wrong or broke we fixed it. Everyone’s intentions were good and the community became increasingly dependent on us and we on them for results that might justify our increasing investment. It was a pity that no one had sufficiently researched the demand for bananas and now the famers are struggling to find buyers willing to pay a fair price.

Looking out over the fields, women and boys are leading donkeys pulling hand ploughs worked by men in kaftans of sky blue, cloud white, and earth brown . And I am thinking this project is like an old Volvo station wagon I once had, first I needed to replace the gear box and I thought after this all would be well for the future but soon it was the electrics that blew, so I fixed them and was sure that the car would now be worry free. But then the dif went and I replaced that and so by the time the power steering stopped working, I was so committed I didn’t really make a decision and when the radiator blew beyond repair I had invested so much that I couldn’t walk away because I couldn’t even sell it for the price of the power steering repair. That question again, what do we hold dear and what do we leave behind?

So as usual, I have no idea what discussion is going to be helpful for us, for them for all of us. So I asked the gathered group what they wanted to achieve and they told me they wanted World Vision to give them more school classrooms and more teachers and to find a buyer who would pay more for their bananas.

I have found that following my instincts is generally better than ignoring them and also that stories are often a first step to something else. So the best thing I could think to do was to tell a story about the opportunities. I said that it sounded to me that they were like some farmers caught in a flood who had climbed onto their thatched roof even as the water was lapping at the edges of the grass thatch. And there was a murmur and several people looked anxiously at the thatch overhead. And I said that the farmers were good Muslims and they prayed to God to save them and they waited in hope. Then after some time some fishermen came by in a canoe and offered to take them to higher ground but it looked risky and they said no, they were waiting for God to save them. A little while later a large tree that had been dislodged from the bank , brushed by the roof and as the waters were rising the famers thought of clinging to the tree and it taking them to safety, but they remembered that they had faith in God and after all, wasn’t it Gods job to save them? Before long the flood swept the roof off the house and it sank and the farmers drowned. There was murmuring in the group and I could sense at this point they could all see themselves swept away in the a swirling muddy river. And I said, the farmers went to heaven and there was Allah, and they said “Blessed Allah, why did you not save us?” And Allah said to the farmers, “Sons and daughters, what do you mean? First I sent you some fishermen in a boat and then I sent you are huge tree to carry you to safety”. And one of the village elders stood up and through translation said that he understood the message and that he saw they needed to use what they had been given and to take some risks to save themselves. So I asked him to chat with the gathered group. I know from experience that nothing is easy, that words are just words particularly from visitor and also that worlds can have power. I have learned that I generally can’t tell the difference. That all of us there that day hold a part of the truth and that all I could do was to try to contribute something that in some way may be helpful.

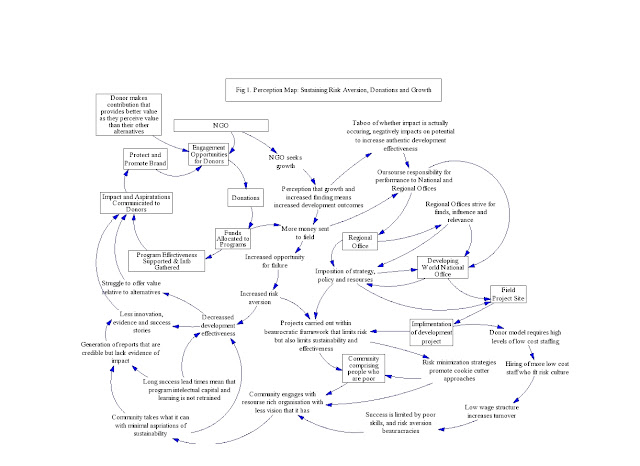

We are so often afraid to lose what we have even when logically there is a real prospect of gaining something of much greater benefit. Believe it or not academics have spent lifetimes researching risk aversion and decision making theory. Loss aversion refers to people's strong preference to avoiding losses over acquiring potential gains. Some studies suggest that fear of losses is twice as powerful, psychologically, as the potential for gains.

I have noticed this when impoverished farmers have a strong reluctance to try new methods or even in some cases work together in new ways. They may recognize the theoretical logic of making a change but they are worried that deviating from their traditions poses a risk of losing the little they have. I have talked with farmers who would rather endure three or four hungry months than risk letting go of tradition trying something new that is likely to mean they will be better off. And it is not hard to see how in an evolutionary way this can make sense, at least they know with the old ways they will survive just like their parents and their parents before them. But there are always exceptions and risk aversion is not true apparently for gold rushes or martyrs.

It is not hard to see how the banana farmers quickly became dependent on World Vision and that when a problem arose they turned to us to fix them. A downward spiral where the more we invested the more we had to lose, the greater the community’s dependence, the less the project was successful the more we invested. And the question arises, “who is trying to sustain what for whom?” We believe in assisting communities increase their social capital and determine their own future and yet our fear of loss and failure can bind us into a spiral in which sustainable development is unlikely. And here that we repeated it for so long must have meant that we weren’t prepared to risk losing the little we had for in the hope that the community would and could find ways to do things themselves. And if we are not prepared to risk loss how can we expect the communities we work with to do the same? It is so seldom about the money and so often about our skills and abilities to take risks with others. And who is it that benefits from taking these stories back to our experts and our supporters.

I like the following quote from the late Amos Nathan Tversky who was one of the pioneers of decision making theory, he said:

“Whenever there is a simple error that most laymen fall for, there is always a slightly more sophisticated version of the same problem that experts fall for ”

Post Script

This was around a year ago and last month I saw part of a report and in it the following excerpt of a speech by one of the Elders from that village near Velingara:

“The village of Foudou exists by the will of World Vision; this is why we must not disappoint. World Vision has set up a banana with a major investment to develop the area economically. Therefore, I would like to return abroad about "Noble Jock" who came when starting the project with BDS Cisse (a new Business Advisor). If I remember correctly, he made us understand that we first had to rely on ourselves before seeking support from others. To return to the signing of this Memorandum of Understanding today between the partner and we Abdou Faye banana producers, I would simply say that we have an incredible opportunity to have World Vision as a "big ship" and Abdou Faye partner as "small ship" and if we are not careful we may lose these two ships if we do not redouble their efforts to succeed. If we fail, we are alone in the ocean and we risk drowning. Through these examples, I was merely a repeat explanations from abroad from World Vision Australia, to say we believe in and enjoy the opportunity we have today to move forward. "

I am not really sure what it means, but I hope it means something true, and if that is the case then that will be a mystery to marvel at and if I am there next year and I have twenty hours to drive to and from Velingara I may just try to find out how things are going.